Many great business ideas begin with a crucial problem that needed solving. While product teams and designers may be eager to build solutions, it pays to not rush your product out the door. If you’ve ever heard the phrase “Give me six hours to chop down a tree and I will spend the first four sharpening the axe,” you might understand why.

Instead of immediately switching into solution-mode, there’s value in taking time to understand a problem from all angles. One of the best ways to properly diagnose and solve problems is to write a problem statement.

In this article, we explain what problem statements are, how to write one, and share a few examples.

Problem statements summarize a challenge you want to resolve, its causes, who it impacts, and why that’s important. They often read like a concise overview managers can share with stakeholders and their teams.

Problem statements help you share details about a challenge facing your team. Instead of rushing to a solution, writing a problem statement enables you to reflect on the challenge and plan your response.

The high-level perspective a problem statement offers lets teams focus on the factors they need to change. Managers also use this top-down vantage to oversee their teams as they work out solutions.

Any time you face a challenge is an opportunity to write a problem statement. You can write a problem statement to improve operations in different contexts. For example, you might use a problem statement to:

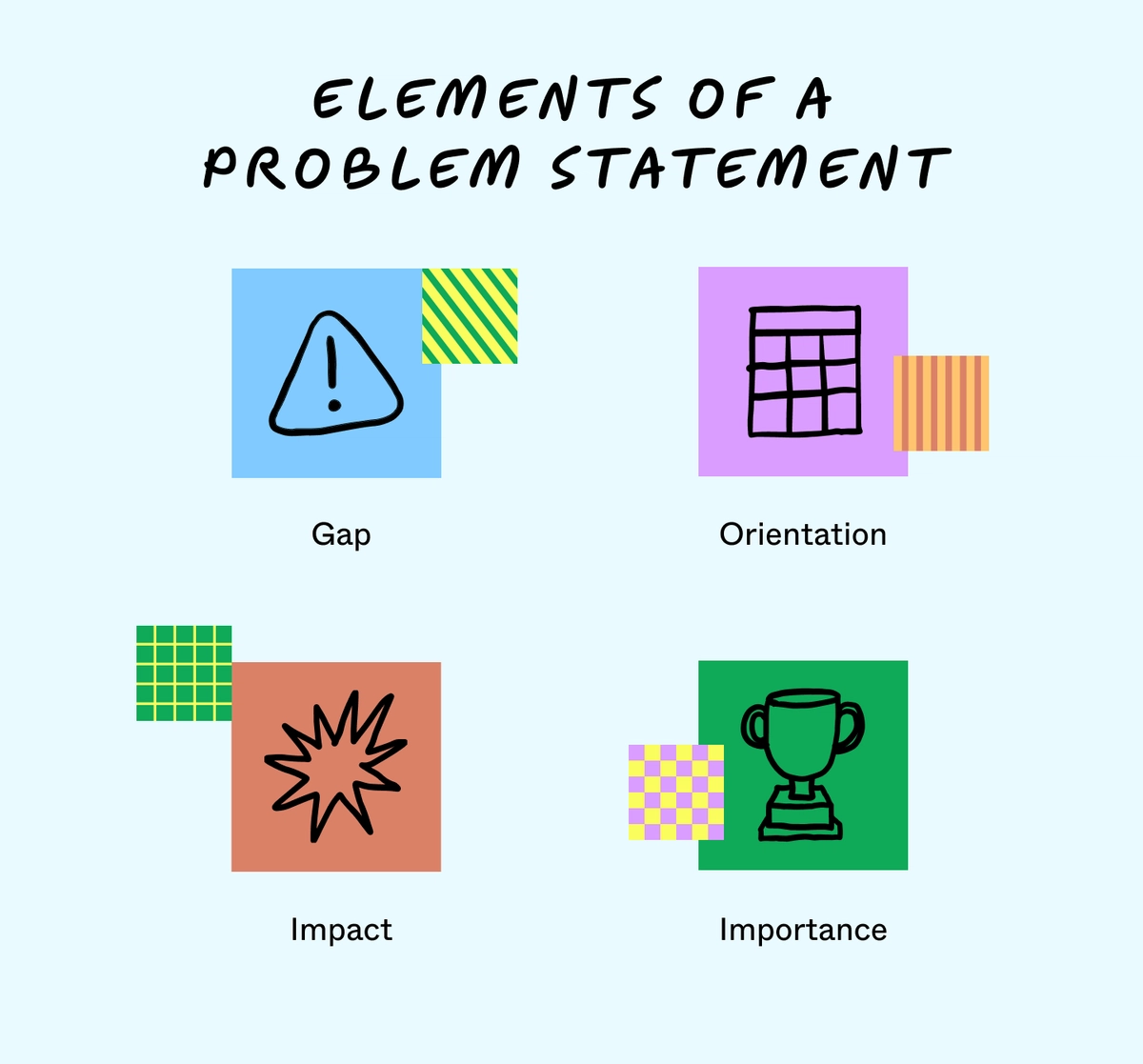

You can break problem statements into a few core elements. While the format of a problem statement is flexible, aim to include the following:

Now that you understand the elements of a problem statement, you can write your own in five key steps.

1. Identify the problem

Start by pointing out an issue and gathering data. Put yourself in the support or production environment where the problem arises and try to experience it firsthand. When gathering data, look for trends or overarching themes—they may help you find the root cause of your problem later.

After seeing the problem for yourself, interview others who know about it. Start with employees who run into the problem or offer support for it. In some cases, they may have a design brief with more information on the issue. Beyond that, customer testimonials and stakeholder interviews can lay out the full scope of your problem.

2. Put the problem into context

Describe how the problem impacts customers and stakeholders. Avoid personal bias and focus on developing a clear perspective. This approach helps prioritize the issue and explain why you need to solve it. If customers can't reach the benefits of your product because of an issue, that's a high-priority concern. If you’ve ever conducted design research, this process should feel similar.

You can put a problem into context by asking:

3. Find the root cause

Ask yourself "why" questions about the problem to find its origin point. Your initial assumptions about a problem might stand in the way, so as you learn more about the issue, don’t be afraid to change how you look at it. You'll get closer to the root cause as you reframe your understanding around these discoveries.

If you need help uncovering the root cause or challenging your initial assumptions, these templates can help:

4. Describe your ideal outcome

Now that you understand the problem, think about your ideal outcome. Whether you're solving a problem with your product or an internal process, remember to avoid scenarios where you put a Band-Aid on the issue. Even if you can avoid specific symptoms in the short term, letting a core problem go unsolved can lead to other setbacks later.

In some cases, you can describe safeguards that let a process work as intended. You can also write an alternative process that avoids the issue altogether. This ideal outcome will inform your goals and objectives in the next step.

5. Propose a solution and outline its benefits

Finally, your problem statement should include solutions to the problem. Including more than one solution gives stakeholders and your team options for deciding your approach. Note the benefits of each solution, highlighting why it stands a chance of working or how it can save on time and costs.

To ensure you arrive at the best solution, be sure to:

Now that you know how to write problem statements, here are some examples.

Suppose you’re a support manager at a midsize SaaS company. Ideally, you want to respond to every support request within a few hours. However, your team can’t reach turnaround times fast enough to meet customer expectations. Start by breaking down the elements of your problem statement:

Now that we’ve laid out the details, we can format it as a problem statement:

Assume you're a project manager at a tech company. You offer a platform that tracks goals and finds inefficiencies in your programmer's workflows. Your leadership wants to release a tool that lets customers estimate the amount of money earned for each workflow issue they correct. However, you aren't sure you have the resources to implement the feature.

With this information, you can turn it into a problem statement:

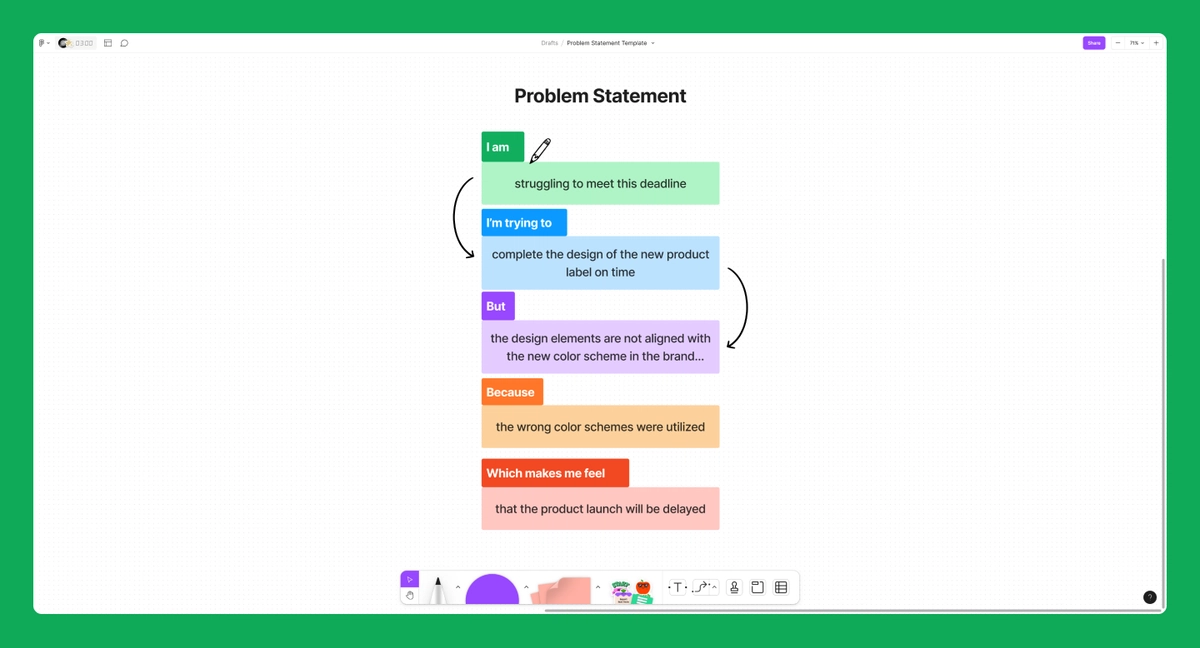

Ready to start writing your own problem statement? Try our problem statement template below.

Project managers used to putting out fires can tell you how much of their job comes down to problem-solving. But before working on solutions, you need to organize your team around a clear problem statement. Find actionable, collaborative solutions by rallying everyone around a shared understanding of a problem.

Once you square away your problem statement, check out our library of over 300 templates. With FigJam, your team can plan and strategize around every step of your project. The right online whiteboard helps you exchange feedback and loop in other teams to find solutions faster.